Website Summary

Our world is today facing historical challenges related to food, nutrition, agriculture, and the environment. Despite significant advancements in this field, global progress in reducing hunger has halted and, in some cases, reversed in recent decades. According to the FAO, a staggering of people going hungry has risen for four consecutive years (FAO et al. 2020). In addition, the COVID-19 led to unprecedented levels of poverty and food security. According to estimates from an IFPRI global general equilibrium model in September 2020, COVID-19 contributed to the deaths of over 150 million people. In this same period, the United Nations World Food Programme forecasted that 130 million people will faced severe hunger (FSIN, 2020).

Overweight and obesity rates are on the rise as a result of marketing and consumer preferences for nonperishable processed foods, a decline in physical activity, and both. With nearly all nations lagging behind in critical nutrition indicators, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of ending hunger by 2030 looks implausibly far off. The biggest threat to future global food systems is still climate change. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2019), increased temperatures and altered precipitation patterns will have a negative impact on the production of critically important foods like maize, wheat, livestock, and fish and seafood. Additionally, an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events is increasing the likelihood of both localised and global food crises. Up to 25–30% of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide come from the food system, which means that we need to cut emissions or even become carbon neutral (IPCC 2019).

In terms of biodiversity, the rate at which natural resources are being depleted is unprecedented. For example, the depletion of natural resources (such as groundwater consumption, deforestation, animal species extraction) is made worse by climate change. Given all of these significant challenges, it is obvious that the ideal food systems should be resilient, inclusive, productive, sustainable, nutrient-rich, and sustainable for the sake of both individual and global health. Food systems are no longer sustainable and unable to meet our diverse needs, according to a number of recent worldwide assessments conducted by interdisciplinary expert panels (FOLU 2019, GLOPAN 2020, Haddad et al. 2016, Willett et al. 2019).

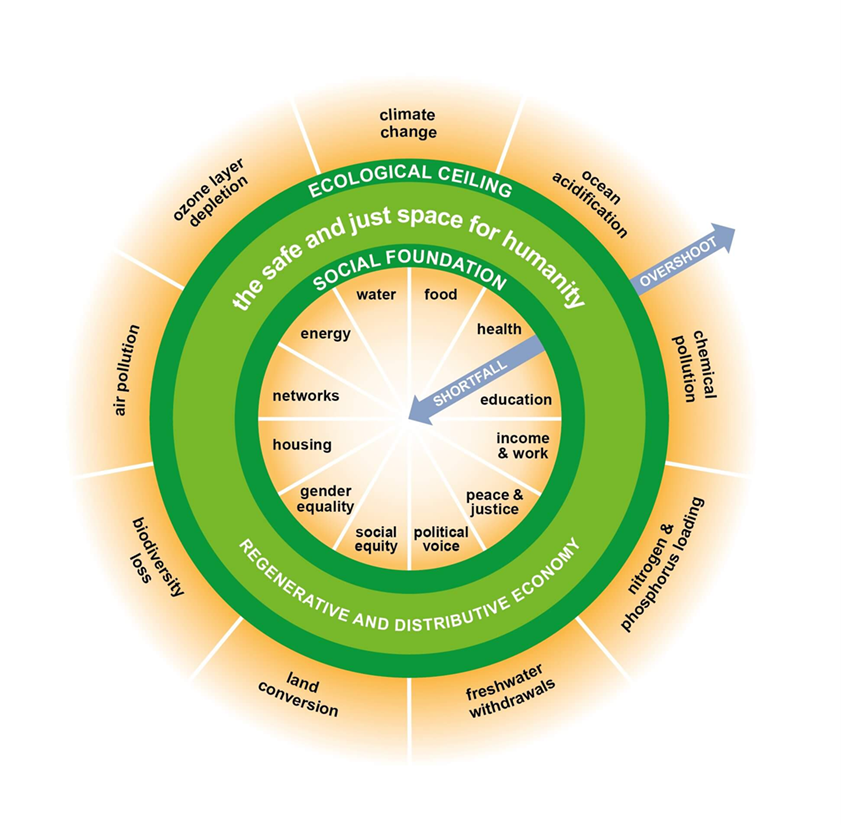

In order to realise food systems and natural resource extraction at a level that meets both individual health, it is important for humanity to position itself in that safe space, as described by Kate Raworth. The safe space in which we do not overshoot our planetary boundaries and we also prevent shortfalls in the inside of the doughnut. Kate Raworth’s model of the doughnut in ‘Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist’ (Raworth, 2017) represents the state of humanity in a single image (see Figure below). The hole at the Doughnut’s centre reveals the proportion of people worldwide falling short on life’s essentials, such as food, water, healthcare, and political freedom of expression—and according to Raworth, a big part of humanity’s challenge is to get everyone out of that hole. At the same time, Raworth argues that we cannot afford to be overshooting the Doughnut’s outer crust if we are to safeguard Earth’s life-giving systems, such as a stable climate, healthy oceans, and a protective ozone layer, on which all our wellbeing fundamentally depends. According to Raworth, humanity’s 21st century biggest goal and challenge is to get into the Doughnut’s safe and just space between these social and planetary boundaries.

Source of figure: Raworth (2017)

At the core of finding that safe and just space for humanity is our ability to adapt to the rapidly changing world of overshoot and shortfall. Nonetheless, historically, it has been argued that structures and mechanisms for mainstreaming adaptation into sectoral planning (such as the food sector) neglect citizen involvement. At the core of adaptation are the stakeholders themselves as citizens. Since food systems have become central to individual and planetary health adaptation, there is the need to consider broader determinants of food security under planetary boundaries. One of such areas of focus that is increasingly receiving attention is citizen behaviour. This embraces demand-side solutions, particularly action on how citizens can change the way they eat to adapt to potential and actual threats posed by climate change and biodiversity loss. This means citizens are not only consumers. They are also active agents who can promote change throughout the food and engage in social and technological innovation in the production, distribution, and most importantly, consumption of food. This denotes citizen engagement that goes beyond mere stakeholder interactions as a technocratic compromise. For sustainability transformation in food practices, both infrastructures and technologies, as well as citizens’ competencies, practices, and world views, need to change to take central stage. Therefore, the aim of this research group is to explore in what ways citizens can play a key role in transforming not only the food system but also the entire breath of socio-ecological interactions that can prevent planetary overshoot and shortfall. Key objectives to attain this aim are as follows:

- Acknowledging what citizens should or are already doing to adapt to changes in socio-ecological systems (remaining within the safe confines of planetary boundaries).

- Recognising the willingness and reluctance of citizens to adapt to changes in socio-ecological systems.

- Identifying citizens’ strengths and weaknesses in adapting to changes in socio-ecological systems.

- An investigation into the inequalities in access to resources required for socio-ecological systems adaptation.